Green Spaces: More Than Just a Pretty Place

“I just spent $15,000 on my new landscape to save $40 a month on my water bill!” Seem efficient to you? It’s a question worth asking, especially as more communities across the country are encouraged to change their landscapes in pursuit of water conservation. While these landscape transformations may deliver some water savings, they often overlook the long-term value of green spaces (also known as green infrastructure) and the hidden costs of removing them. Whether it’s a front yard, a public park, or a commercial landscape, the transformation of green spaces into rock-mulched beds, artificial turf, or hardscape can lead to negative unintended consequences—higher energy bills, hotter neighborhoods, increased stormwater runoff, and diminished public health outcomes.

Having said that, grass certainly doesn’t belong everywhere, and low water use plant landscapes have their place, particularly in areas where water is scarce, and maintenance is a challenge. But a growing body of research shows that reducing or eliminating green spaces leads to higher financial, environmental, and social costs in the long term.

Research Highlights

- Hardscape, artificial turf and rock-mulch beds lead to hotter neighborhoods, stormwater runoff and diminished public health.

- The financial realities of landscape transformation are underestimated.

- Trees, plants and turf play a role in improving air quality and climate regulation.

- Well maintained green areas are associated with increased neighborhood trust.

Lately I’ve been exploring how green spaces—including turfgrass and other vegetated areas—are essential for building livable, resilient communities. There are real-world trade-offs to consider when green spaces are reduced or eliminated so balanced, data-informed approaches are critical for water managers, planners, and homeowners alike.

The True Cost of Landscape Transformation

The financial realities of landscape transformation are often underestimated in water conservation planning. While turfgrass removal programs are widely promoted as cost-effective solutions, the switching costs—the expenses associated with removing turf and replanting with drought-tolerant alternatives—can be significant. For example, the average cost to remove and re-landscape a standard residential yard can exceed $15,000, yet the monthly water bill savings may amount to only $30–$40 (Lawn Love, 2024; Sovocool, 2005). This means a homeowner could wait 30 years to recoup their investment, even in high-cost water regions. This tradeoff becomes even less justifiable when plant mortality and replanting costs are factored in—a common issue with xeriscapes that are poorly designed or improperly maintained (St. Hilaire et al., 2008).

In addition, all plants require an establishment level of irrigation for 1 to 2 years, and without proper installation and aftercare, these landscapes often fail, requiring additional investments in maintenance and plant replacement (Sun et al., 2012). And low-water landscapes are definitely not maintenance-free. They require weed control, mulching, and seasonal pruning just like any other landscape, which all add to the long-term costs of changed landscapes.

For water utilities and policy makers, these realities should be leading to smarter program design. Rather than incentivizing blanket turfgrass removal programs, they should focus on outcome-based water savings. And there should be support for regionally appropriate, low-input grasses and landscape transformations that have verified performance improvements (EPA WaterSense, 2023).

A balanced approach—one that retains functional green spaces while improving efficiency—can offer a better return on investment for communities, households, and the environment alike.

The Benefits of Green Spaces

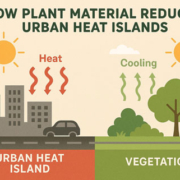

Green spaces (also known as green infrastructure), including turfgrass and other vegetation, provide critical environmental services to urban and suburban communities. One of their most important benefits is cooling through evapotranspiration—the process by which water evaporates from soil surfaces and transpires from plant leaves—removing heat from the surrounding air. Studies have shown that green spaces can be significantly cooler than adjacent hardscapes, helping to mitigate urban heat island effects, reducing air conditioning (and electricity) demands, and lowering the health risks associated with extreme heat events (Shashua-Bar et al., 2009).

Densely planted landscapes also contribute to stormwater management by slowing stormwater flow, reducing runoff, and increasing infiltration rates. Unlike hardscapes or artificial turf, which shed water quickly and increase the burden on municipal drainage systems, densely planted landscapes can slow water movement and help filter out pollutants, improving downstream water quality and reducing flood risk.

Turf and trees also play a role in improving air quality and climate regulation. Grasses and other plants trap airborne particulates and absorb carbon dioxide through the process of photosynthesis. And well-managed lawns have been shown to sequester up to one metric ton of carbon per hectare per year, contributing to climate mitigation efforts (Qian et al., 2010).

These environmental services make the strong case for recognizing green spaces as functional infrastructure—not just pretty places.

The Connection Between Green Spaces and Mental Health

Did you know that green spaces are increasingly recognized as essential components of public health infrastructure? Exposure to green vegetation—even just looking out a window—has been shown to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression, while also improving cognitive function, attention span, and emotional regulation. In one of the earliest and most influential studies of green space effects on health, Ulrich (1984) found that hospital patients who had views of trees from their windows recovered more quickly and required less pain medication than those with views of a brick wall.

More recent research has expanded on these findings, showing that people who spend at least two hours per week in green spaces report significantly better mental and physical well-being (White et al., 2019).

However, access to green space is not the same for everyone. Lower-income and marginalized communities often have fewer parks, tree-lined streets, or natural views—compounding environmental stressors with social disadvantage. And this lack of access can contribute to health disparities, especially as urban density increases.

For urban planners and municipalities, the take-home message is clear. Green space should be treated as a form of public health infrastructure. Parks, greenways, and even modest residential landscapes can promote psychological resilience, especially when designed with accessibility and inclusivity in mind. As Bratman et al. (2019) emphasize, integrating nature into cities is not a luxury—it’s a necessity for collective well-being.

Communities with Green Spaces are Stronger

The positive mental health implications of green spaces aren’t the only benefit of these spaces. Green spaces, for example, actively help build safer, more connected communities and numerous studies have shown that well-maintained green areas are associated with lower crime rates and increased neighborhood trust. In a foundational study, Kuo and Sullivan (2001) found that Chicago residents living near greener common areas reported fewer violent crimes and greater feelings of safety and cohesion. These spaces naturally promote informal social monitoring and encourage outdoor interaction between neighbors, both of which foster a stronger sense of community.

Green spaces also function as important community gathering places, especially when designed to be inclusive and welcoming. Parks, community gardens, and pocket green spaces support cultural events, children’s play, and intergenerational interaction. Well-used parks also help cultivate social capital, improving neighbor friendships, and making communities more resilient (Peters et al., 2010).

However, not all green spaces are created equal. To fully realize their potential, green areas must be accessible, equitably distributed, and well-integrated with schools, transit, and housing. Design choices like shaded seating, ADA-compliant paths, and multilingual signage enhance usability and reflect community diversity.

Local governments should consider green spaces as essential civic infrastructure that supports public safety, health, and inclusion and an investment well worth making.

What About the Economics of it All?

Green spaces don’t just look good—they also make good economic sense because well-designed green spaces are linked to increased property values, which can expand a municipality’s tax base. Studies have shown that proximity to parks and other well-maintained green areas can increase residential property values by as much as 20%, benefiting both homeowners and local governments (Crompton, 2005). This boost in valuation contributes directly to local revenue streams, helping to fund services without raising tax rates.

Green infrastructure also generates energy savings and associated cost savings. This is because landscaped areas with turfgrasses, trees, and shrubs reduce surface and ambient temperatures, which helps lower cooling demands in adjacent buildings. Akbari et al. (2001) found that increasing urban green space significantly reduced peak electricity use, offering long-term savings for both property owners and utilities. At the time of the study, they found that energy use for air conditioning could be reduced by 20% nationally with a potential cost savings of $10B annually. Those numbers would likely be much higher if the study were repeated today given the increased urban heat island effects we’re now dealing with.

For businesses, green spaces offer much more than beauty—they drive foot traffic and enhance the overall customer experience. Shaded walkways and planted medians, for example, make shopping areas more pleasant, and they increase the amount of time customers spend inside businesses and the amount they spend.

These benefits suggest a (literally) valuable opportunity for utilities and municipalities. Rather than promoting total turfgrass removal or gravel-intensive xeriscapes, they should incentivize water-efficient, highly vegetated landscapes that provide multiple environmental and economic services.

Designing Smarter Landscape Programs

I would like to see smarter, more sustainable landscape programs that start with policies that balance conservation with function. Instead of removing turfgrass indiscriminately, communities could promote “turf with purpose”—that is, preserving grass where it serves functional, social, and ecological roles.

Turfgrass is ideal for recreation, erosion control, cooling, and improved stormwater infiltration, especially when integrated into multi-use spaces like parks, schoolyards, and civic grounds (Braun et al., 2024). So why not recognize that fact instead of keeping a laser-like focus on turf removal? Instead, policymakers and water authorities should support hybrid landscapes that combine low input turfgrasses, regionally appropriate perennials, and smart irrigation systems. This approach would maintain the benefits of green spaces while conserving water.

The key is shifting from prescriptive plant lists to outcome-based programs that focus on measurable water savings—not just the appearance of water savings. Some xeriscapes fail to deliver water savings due to poor plant selection or management, underscoring the need for flexibility and performance tracking (Sun et al., 2012).

Of course, like most things in life, collaboration is essential. Water conservancy districts, Cooperative Extension services, and municipal planning departments should work together to guide residents, HOAs, and developers in adopting sustainable landscaping practices. One great example is the Localscapes™ approach which was developed in Utah. This program encourages blending turfgrass, ornamental plantings, and efficient irrigation into cohesive, attractive, and climate-appropriate designs that retain all the environmental benefits of green spaces and save water (Localscapes™, 2025).

By supporting functional green space and encouraging integrated solutions, communities can reduce water use without sacrificing the livability, beauty, or ecological value of their green spaces.

Conclusion

Green spaces are not frivolous “extras”. They are critical infrastructure that supports environmental resilience, public health, and community cohesion. And while landscape transformation programs may promise quick water savings, the long-term economic, social, and ecological costs of losing green spaces often outweigh this benefit.

From cooling urban neighborhoods and managing stormwater to improving mental health and strengthening neighborhood relationships, green spaces deliver measurable benefits that can’t be replicated by sparsely planted gravel landscapes or artificial turf.

With smart irrigation technologies, climate-appropriate plants, and informed landscape designs, we can have landscapes that are both beautiful and responsible. The key is balance—not the elimination of whole categories of plant material.

We don’t just live around nature—we live with it, if we’re lucky. And as communities grow and climates shift, preserving and enhancing green spaces is one of the smartest investments we can make for a healthier, more livable future.

References

Bratman, G.N., C.B. Anderson, M.G. Berman, B. Cochran, S. De Vries, J. Flanders, C. Folke, H. Frumkin, J.J. Gross, T. Hartig, P.H. Kahn Jr., M. Kuo, J.J. Lawler, P.S. Levin, T. Lindahl, A. Meyer-Lindenberg, R. Mitchell, Z. Ouyang, J. Roe, L. Scarlett, J.R. Smith, M. Van Den Bosch, B.W. Wheeler, M.P. White, H. Zheng and G.C. Daily. 2019. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Science Advances 5(7):eaax0903.

Crompton, J.L. 2005. The impact of parks on property values: empirical

evidence from the past two decades in the United States. Managing Leisure 10(4):203-218

Kuo, F.E. and W.C. Sullivan. 2001. Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime? Environment and Behavior 33(3):343-367.

Lawn Love. 2024. How Much Does Xeriscaping Cost in 2025? Retrieved April 20, 2025. https://lawnlove.com/blog/xeriscaping-cost/.

Localscapes. 2025. About Localscapes™. Retrieved April 20, 2025. https://localscapes.com/about.

Peters, K., B. Elands, A. Buijs. 2010. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 9(2):93-100.

Qian, Y., R.F. Follett and J.M. Kimble. 2010. Soil organic carbon input from urban turfgrasses. Soil Science Society of America Journal 74:366–371.

Shashua-Bar, L., Pearlmutter, D. and E. Erell. 2009. The cooling efficiency of urban landscape strategies. Landscape and Urban Planning. 92:179-186.

Sovocool, K.A. 2005. Xeriscape conversion study: Final report. Southern Nevada Water Authority. Las Vegas, NV.

St. Hilaire, R., Arnold, M.A., Wilkerson, D.C., Devitt, D.A., Hurd, B.H., Leskovar, D.I., White, R.H. and D.F. Zoldoske. 2008. Efficient water use in residential urban landscapes. HortScience. 43(7): 2081-2092.

Sun, H., K. Kopp and R. Kjelgren. 2012. Water-efficient urban landscapes: Integrating different water use categorizations and plant types. HortScience 47(2):254-259.

Ulrich, R.S. 1984. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 224(4647):420-1.

White, M.P., I. Alcock, J. Grellier, B.W. Wheeler, T. Hartig, S.L. Warber, A. Bone, M.H. Depledge and L.E. Fleming. 2019. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Scientific Reports 9:7730.